In September 2024, the Federal Reserve’s 12-member Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voted to lower benchmark interest rates for the first time since March 2020.

The 50 basis point rate cut brought the target Federal Funds Rate down from a range of 5.25%–5.50%, a rate the central bank had maintained since July 2023, to 4.75%–5.00%.1 This half-point cut also marked a long-anticipated end to the Fed’s fastest and most aggressive rate hike cycle since 1982.

But the FOMC was far from finished: it would conclude 2024 by delivering two more 25 basis point rate cuts, once each in its November and December meetings. At the time of writing in January 2025, the Fed’s benchmark range stands at 4.25%–4.50%,1 a full percentage point lower than the cycle peak the FOMC departed from just several months prior.

Looking ahead, it appears that further rate cuts could be in store. Notes from the Fed’s December 2024 meeting revealed that most FOMC members expect another two quarter-point rate cuts by the end of 2025, and potentially further declines into 2026 and 2027.2

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (December 2024)

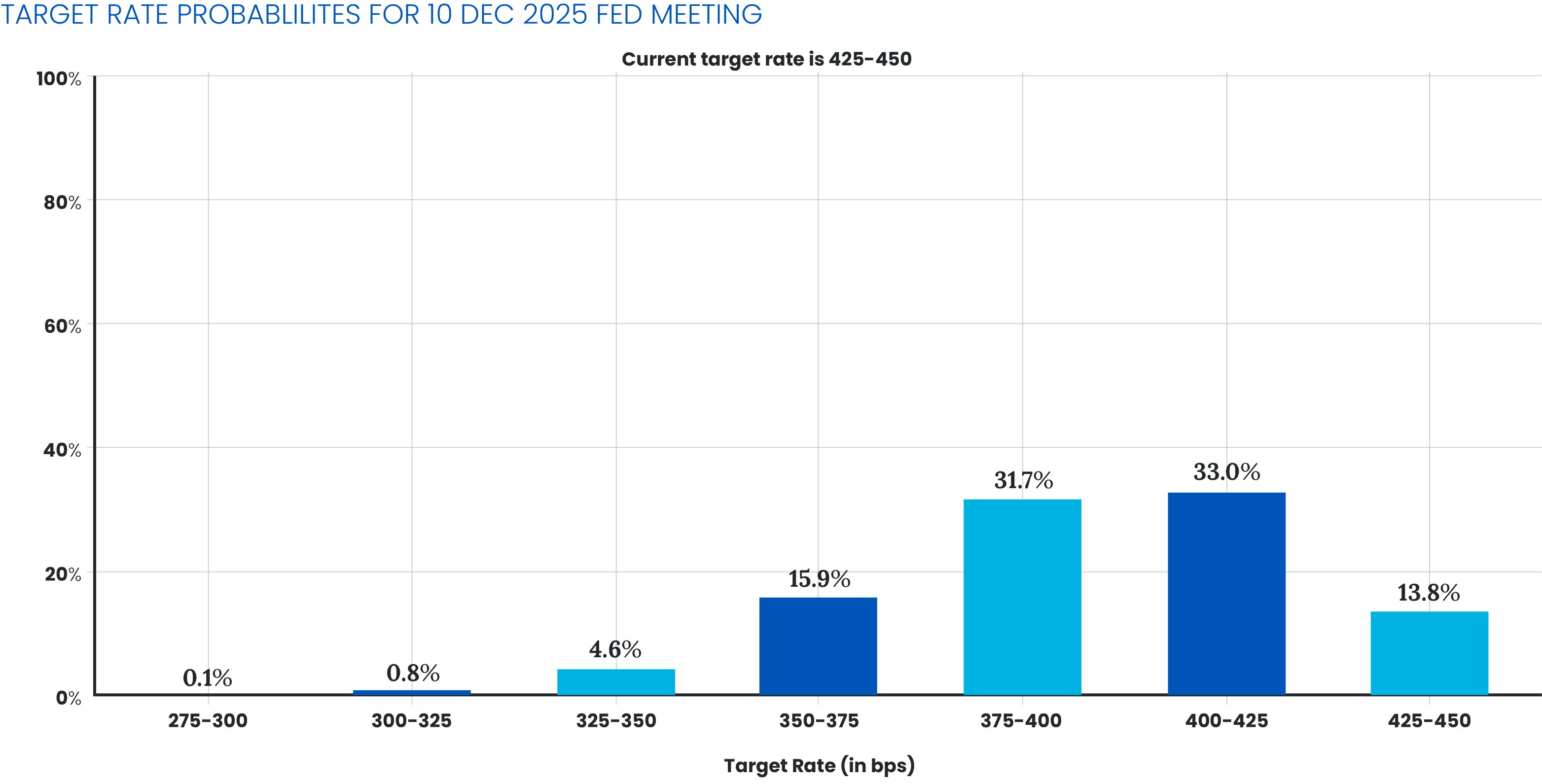

The market paints a similar—though not identical—picture. As of January 9, 2025, Fed Fund futures contracts are pricing in a 33.0% probability of a single quarter-point rate cut by the end of this year. Meanwhile, futures assign a marginally lower 31.7% probability to the FOMC’s own projection of a 50 basis point decline by December 2025.3

Could there be more than two rate cuts over the next twelve months? It’s unlikely—but not impossible. With a 15.9% chance of a 75 basis point decline and a 4.6% probability of a full percentage point cut by the end of 2025, the consensus view, at least for now, seems to be a matter of when (and how sharply) the Fed will lower rates—not if.3

Source: CME FedWatch (January 2025)

How Will Private Credit React to Falling Yields?

Declining benchmark interest rates are generally seen as advantageous to borrowers and unfavorable to lenders. Private credit investors, either directly or via a fund, make direct loans to sponsors and corporate borrowers—so, like other forms of debt, the asset class is sensitive to broader interest rate movements.

Specifically, falling yields pose headwinds to private credit because most funds borrow at fixed rates and lend at floating rates. When rates decline, the spread between the rate at which the fund borrows at and the rate that it is able to lend at compresses; this lowers income available to investors and reduces total returns.

Of course, the asset class is not monolithic. Some managers may choose to do the opposite, borrowing at floating rates and lending out at fixed rates. This arrangement is sometimes favored by asset-backed private credit lenders whose borrowers—often developers or builders—prefer the predictability of fixed-rate, fixed-term loans.

For these funds, falling rates could enhance returns, rather than hobble them. As broader yields fall, the floating rates at which these funds borrow at could decline in tandem; at the same time, yields from previously closed fixed-rate loans will remain level. This combination results in an expansion in the yield spread that investors can capture.

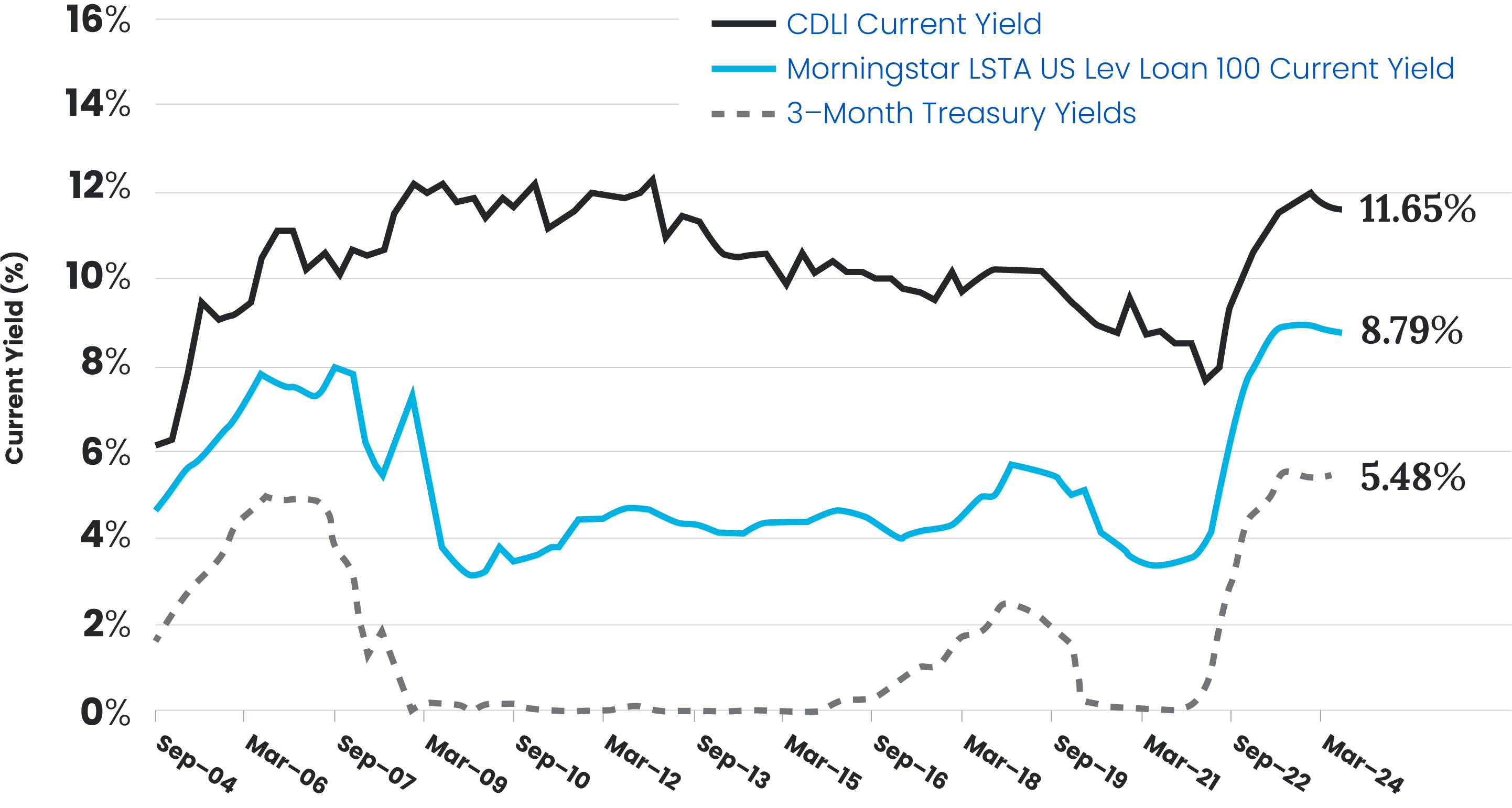

To strengthen this argument, there’s a chance the asset class as a whole could prove resilient in the face of declining yields, even if investors completely ignore how any given fund structures its assets and liabilities. The protective factor here, of course, is the significant spread—often three to six percentage points—between short-term treasuries and high-yield debt.4 Loans underwritten by private credit funds belong in the latter category because, unlike treasuries, they are illiquid, feature longer maturities, and are subject to credit risk.

Source: Cliffwater (October 2024)

As past data shows (and intuition suggests), there is often a positive correlation between treasury yields and private credit yields: when treasuries rise, private credit rates typically do as well; when one falls, the other tends to follow suit.5

But just as crucial is the observation that the yield spread between treasuries and private credit is not static. This means that a sufficiently tightening spread between the two instruments could cause correlations to break. In other words, private credit yields could fall even as treasuries rise; conversely, a dramatically widening spread could lead to rising private credit yields even as treasuries decline.

To take things a step further, the existence of a substantial spread itself—never mind its direction—is enough to shield private credit yields from the whiplash of FOMC rate decisions. As an August 2024 publication by the Federal Reserve itself explains, “...when rates are decreasing…the high spreads above base rates that are featured in direct loans [i.e. private credit] insulate[s] returns, acting as an effective floor. Moreover, high spreads relative to base rate changes lead[s] to overall less volatility relative to expected returns, which is attractive to investors.”6

Could the Fed Raise Rates Instead in 2025?

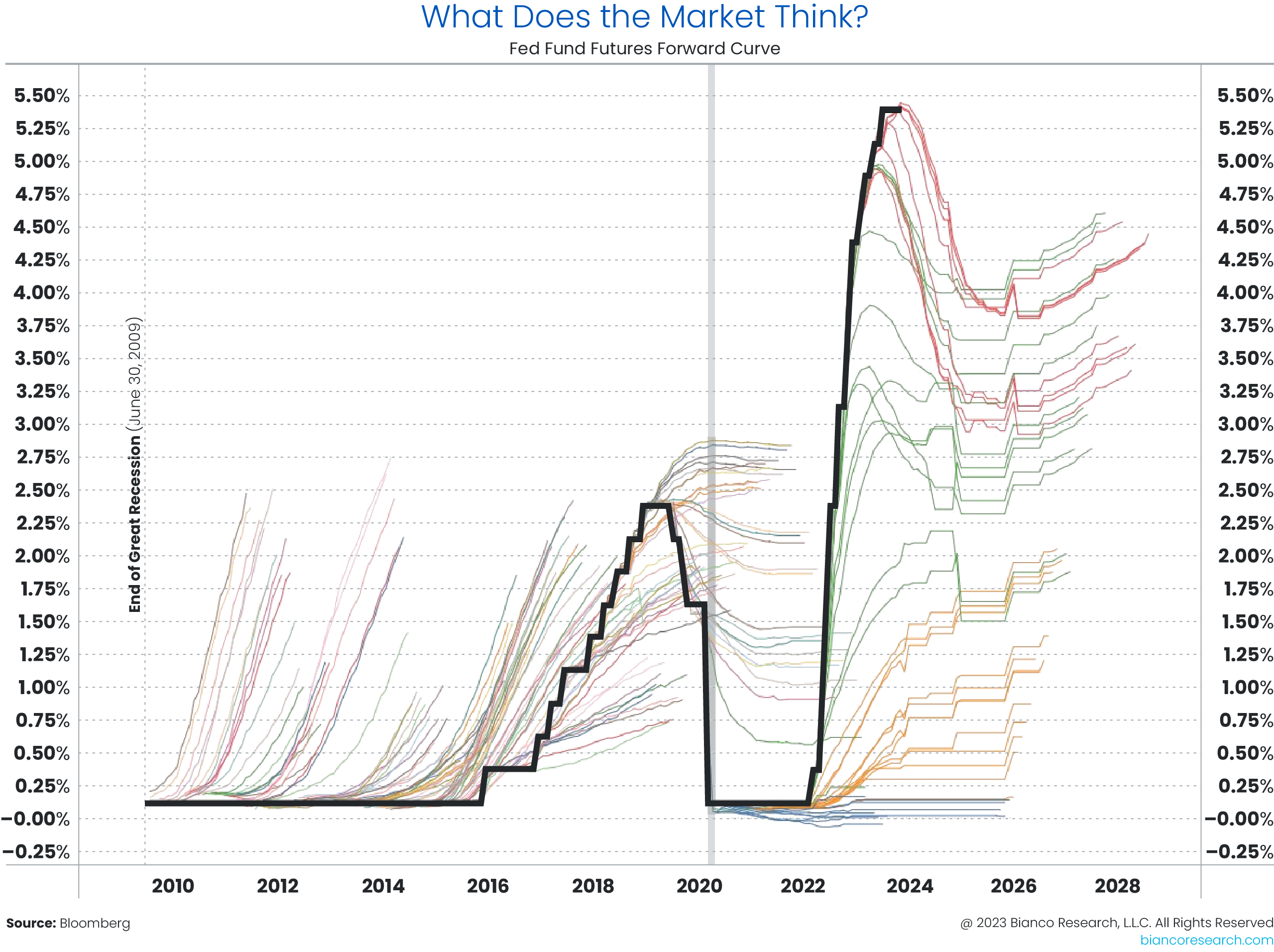

It would be remiss not to mention the possibility that the Fed could reverse course and raise rates into 2025. The market, after all, scarcely produces accurate forecasts about the trajectory of interest rates, especially over the medium- and long-term.

Source: Bianco Research (January 2024)

Besides, a Fed U-turn has happened before and could realistically occur again. Most recently, the FOMC, under then-chair Alan Greenspan, hiked rates by 175 basis points across six separate occasions between June 1999 and May 2000 almost immediately after slashing rates by 75 basis points between September and November 1998 in response to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis and the subsequent collapse and bailout of Long Term Capital Management (LTCM).7

Some experts forecast that today’s Fed under Jerome Powell could make a similar about-face. Torsten Sløk, a partner and the chief economist at alternative asset manager Apollo Global Management, believes there is a 40% chance the central bank could raise interest rates from current levels. “The strong economy, combined with the potential for lower taxes, higher tariffs, and restrictions on immigration, has increased the risk that the Fed will have to hike rates in 2025,” he explains.8

If this prediction materializes, what will be a risk for borrowers could spell opportunity for private credit lenders. Higher rates at the short end of the treasury yield curve could elevate the yields of the longer-term treasuries used to price private loans. This, in turn, could help sustain the high yields earned by private credit investors for longer.

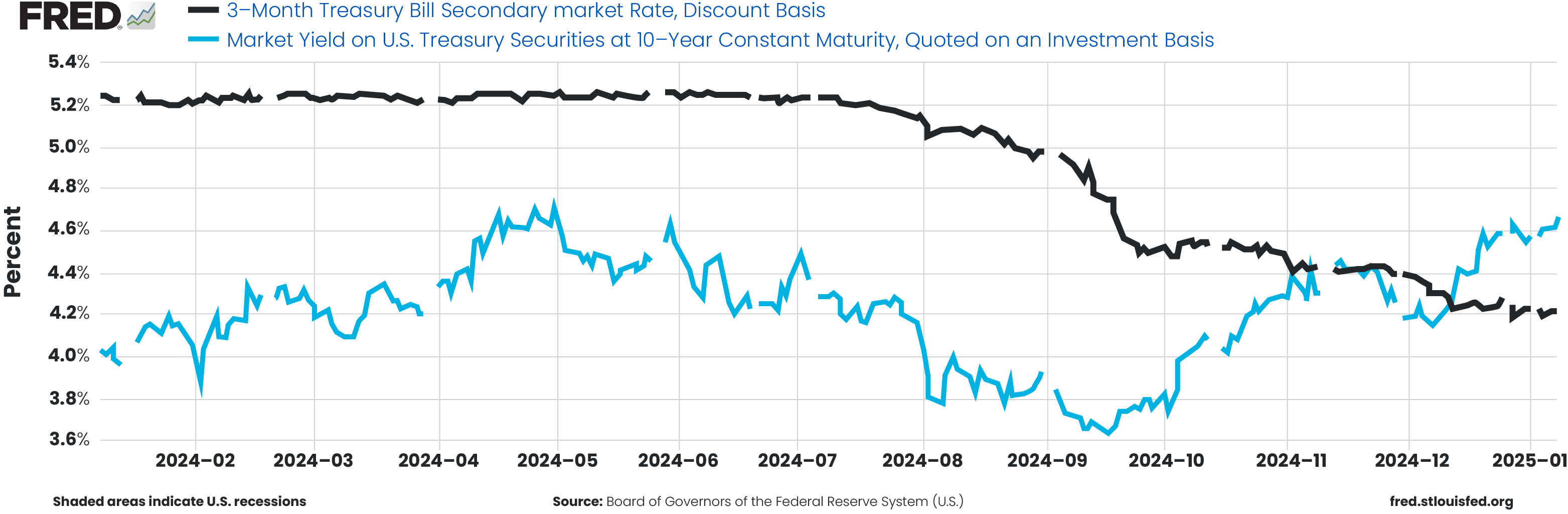

Given the recent divergence between 10-year treasury yields and the Fed’s policy actions,9 however, perhaps one could even argue—albeit not without some controversy—that the FOMC’s forthcoming rate decisions can be safely ignored for the time being.

Source: St. Louis Fed (January 2025)

A prolonged decoupling between the general direction of short- and intermediate-term treasuries has historically been uncommon, though, so either the Fed or the market will win out eventually. The next several months will reveal whether the Fed made a premature decision to slash rates in the back half of last year, or if fears of an overheating American economy—as implied by rising 10-year yields—will come to pass.

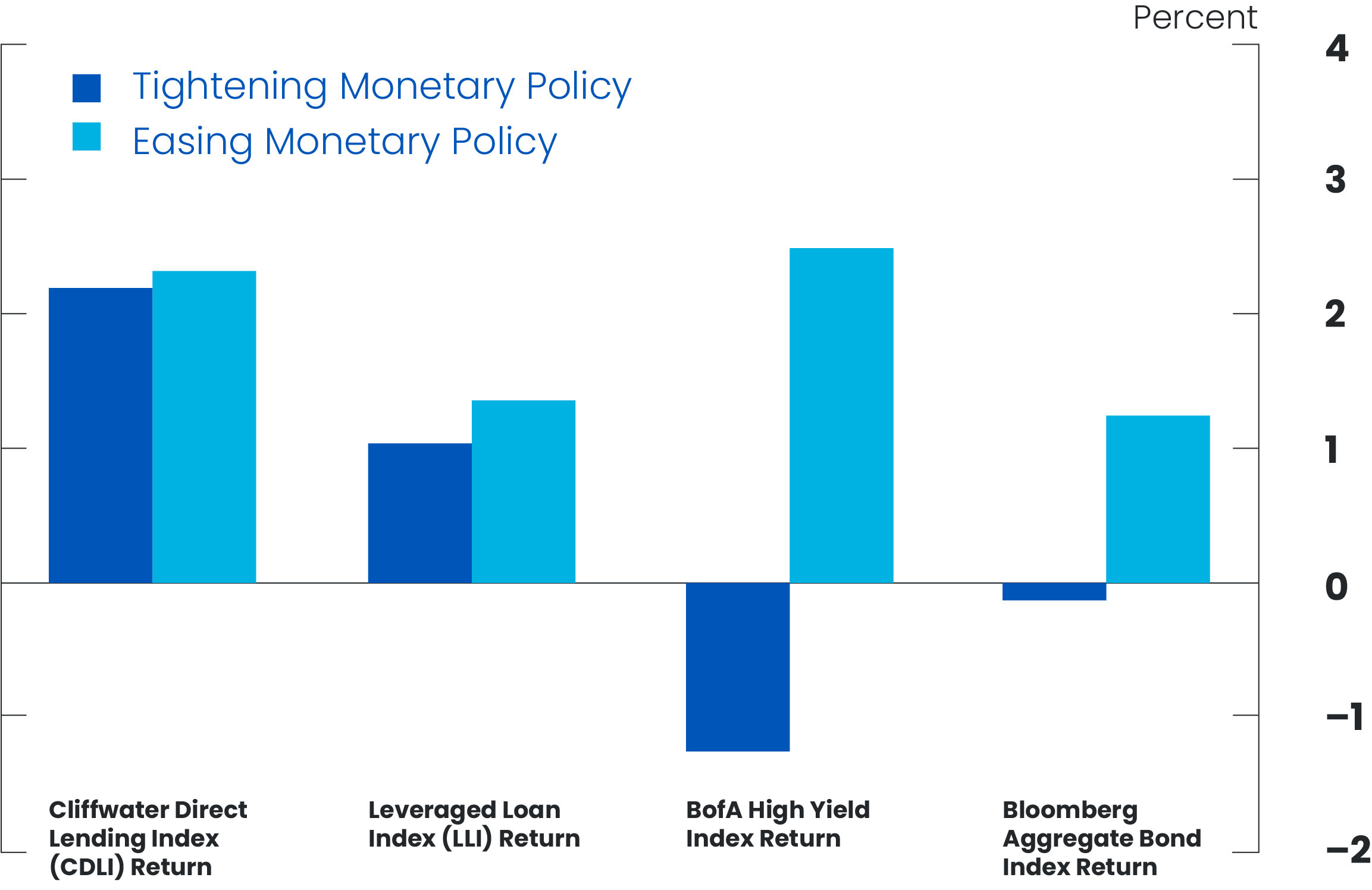

Then again, private credit investors arguably have little to fear—regardless of where rates head next. As the same Fed report mentioned previously argues, “direct lending's [i.e. private credit’s] return performance compares favorably to leveraged loans and high-yield bonds in both easing and tightening monetary policy environments.”6 This stands in sharp contrast to publicly-traded investment-grade and high-yield debt, which tends to fare well only during easing cycles.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (August 2024)

Private credit’s resilience across fluctuating monetary policy conditions has made it an attractive asset class among investors who seek elevated and consistent yields in the face of constant change. While no asset class is fully inoculated against all macroeconomic risks, it stands to reason that private credit investors could fare reasonably well—regardless of the Federal Reserve or the bond market’s next moves.